I’ve been running Windows 10 on a test computer via the Windows Insider Program for a couple of months now. A few days after the official release on July 29, Windows 10 updated itself to build 10240, which was the build designated by Microsoft as the release version. At the time, the only change I noticed was that the message at the lower right of the screen was gone. The message previously showed that I was running a Windows Insider build. As of August 27, I’m on the build 10532 Preview/Beta, and the ‘Evaluation’ message is back.

Regardless, the version I’m running is close enough to the official release version that I think it’s safe to talk about my initial observations.

Good stuff

Performance

Despite the fact that my test PC is several years old, has only 2 MB of RAM, and I’m using the motherboard’s built-in display hardware, Windows 10 runs very smoothly. It doesn’t have any trouble running anything I’ve thrown at it, aside from one game (a Windows App) that apparently has some display issues.

System monitoring tools

The new Task Manager and Resource Manager are a huge improvement over the previous tools. These were actually introduced in Windows 8.x, but if you haven’t used that O/S, they will be a very welcome change.

Explorer

Windows Explorer, particularly the dialogs shown for copying, moving and deleting files, is much improved. In my opinion, those file operation dialogs are now what they should have been in Windows 95: actions can be interrupted, paused and resumed; there’s a ton of detail provided, including a speed graph; and errors can be ignored, allowing operations to continue.

Users and networks

Windows 10 includes better handling of multiple users and networks. There are new ways to log in, including using a camera to detect and identify your face, and short numeric codes (PINs).

Edge

Microsoft’s new web browser, Edge (aka Project Spartan), is getting rave reviews. It’s lean and fast, and supports current web standards. Gone are the days of slow, buggy, incompatible Internet Explorer. It’s geared to mobile devices, and there are relatively few ways to customize it, but if those things don’t bother you, you’ll probably like it.

Media

I never did use Windows Media Center, preferring instead the much more powerful and flexible XBMC, now called Kodi. Despite my test computer’s integrated graphics chipset, I can play HD media without any framerate issues, even the framerate-killing bird flock scenes from Planet Earth.

The nasty vertical tearing I previously saw when using Netflix in Firefox (via Silverlight) is completely gone. It’s hard to know exactly why, but it was a huge problem when I was running Windows XP on the test PC, and that problem is now gone.

Not-so-good stuff

As with any new operating system, there are numerous minor issues with Windows 10. For example, default applications can no longer be set programmatically, which has all the browser makers understandably peeved, despite the improvement in security.

But there are two big areas of concern for Windows 10: privacy, and the new user interface.

Privacy: general issues

Many of the privacy issues in Windows 10 are also typical of smartphones. But people seem less likely to be concerned about these same issues on their phones. I think there are a couple of reasons for this: people generally think of their phones as appliances, and mobile systems and apps are more up-front about the access they require. One could argue that Windows 10’s Terms of Use is perfectly up-front, but that’s a blanket coverage that most people only see once: it’s a legal document, it’s very long, and it can be skipped easily. Phone apps tell you only what you need to know, usually in very clear terms, and they do it before they are installed.

In general terms, Windows 10’s privacy issues can be categorized as follows:

Watching user activity and data

By default, Windows 10 watches what you do. It analyzes your documents and communications, with the aim of improving your overall experience of the O/S. For most users, this is presumably a reasonable trade-off: they are okay with Windows stalking their activity if it means things generally work more smoothly. Especially if the collected information is never stored or transmitted.

Storing information about user activity and data locally

Of course, all that information would last only until the next reboot if it’s wasn’t stored somewhere, and you can be sure Windows 10 is squirreling it away on your hard drive. But as long as this data is secure, and is never sent anywhere, it still seems like a reasonable price to pay for a better Windows experience.

Transmitting user information to Microsoft servers

This is where most people start to get uncomfortable. It seems clear that Microsoft isn’t satisfied with stalking us locally. Windows 10 transmits information about user activities to Microsoft servers, where it is presumably used in a variety of ways. There’s no reason to assume that this information is then used for evil, but there’s also no way to know for sure.

Anonymity of stored and transmitted user information

On the other hand, if all this user information is properly anonymized, meaning that it can never be associated with any specific person, is this really a problem? That depends on your perspective. If Microsoft is using this material to improve the user experience (for example by detecting and tracking bugs), then it seems like a reasonable trade-off. But they are almost certainly also feeding this data into their advertising infrastructure, in order to more accurately target ads, and to make their ad space more valuable.

User approval and notification

I believe that a lot of this would be acceptable to users if Microsoft was more up front about it. When Windows is about to do something that could be characterized as a privacy breach, it should alert the user: “Windows wants to send your browser history to Microsoft. Is that okay?” If these alerts also included a “Remember my answer” checkbox, disruption to the user would be minimized.

Instead, what we get is a huge Terms of Use document when we install Windows or start using it for the first time. All this privacy-compromising behaviour is described in that document, but nobody ever reads these things, and it only appears once. After that, your only option is to locate the associated Windows settings and disable them, and hope that covers everything.

Keeping user information for any significant length of time

If all this user information is properly anonymized, Microsoft can keep it forever as far as I’m concerned.

Providing user information to authorities

Microsoft has stated officially that they will hand over any and all information they have, about any user, to legal and other authorities. All the authorities have to do is ask for it. This is a huge problem for many people. As long as Microsoft is just trying to make things work better, and doing everything it can to maintain my privacy, I’m willing to let them peek at my activities. But their willingness to hand over my private information to the authorities crosses a line. This is the point at which I balk, and start disabling things in Windows 10.

Microsoft’s intent

It’s probably a good idea to step back at this point and assess your feelings about Microsoft’s intentions. Microsoft insists that all they’re doing is trying to improve the user experience. But we also know that Microsoft is moving toward a more advertising-centric sales model, in which the more they know about their users, the more money they can make.

You should also recognize that even if Microsoft’s intentions are not evil, your information could end up in the wrong hands by way of a systems breach, or simple incompetence. Do you trust Microsoft’s minions to never ever make a mistake with your information?

Privacy: specific issues

Beyond the general privacy concerns outlined above, some specific issues have come to light in connection with Windows 10.

Retrofitting earlier versions of Windows

Microsoft wants earlier versions of Windows to do many of the things that have people concerned about Windows 10. To that end, Microsoft is pushing a series of updates to Windows 7 and 8.x via Windows Update. None of these updates are required, but some of them get installed automatically. Thankfully these updates have been identified and their effects documented, so it’s easy to get rid of them.

Forced updates

If you’re running a Home version of Windows 10, system and application updates will be installed on your computer whenever Microsoft wants to install them. If you’re using a Pro version, you can postpone any individual update for a few weeks, but not indefinitely. Microsoft is probably doing this for several reasons:

- To improve the security of Windows 10 computers worldwide. As long as updates are optional, some users will continue to avoid and/or neglect installing them. Forcing updates eliminates this security weakness. It’s a laudable goal, and an increasingly common approach used by other software makers. But I would still prefer to have a choice.

- To allow Microsoft to push out advertising, and changes to the O/S related to advertising, without any choice for the user. Being able to consistently force advertising down our throats increases the value of the advertising space Microsoft is selling for Windows.

- To allow Microsoft to detect and disable any software or hardware they determine to be incompatible, harmful, or unlicensed.

I consider this a privacy issue, in the sense that I don’t want someone at Microsoft to decide what happens on my computer.

Using your computer to distribute updates

By default, Windows 10 uses your upload bandwidth to distribute updates to other user’s PCs. This feature is arguably very sensible, in that it greatly improves the efficiency of update distribution. But I still don’t want it to happen, primarily because my Internet connection is asymmetrical, meaning that I have very limited upload bandwidth available. This is true of most Internet connections, including yours. Thankfully, this feature can be disabled.

Advertising

Windows 10 has more advertisements, in more places, than any previous version. If you don’t like the sound of that, you should probably stay away. True, the ads only show up in certain places, and they’re mostly fairly unobtrusive, but that seems likely to change. One of places ads appear is Solitaire, which no longer comes with the O/S, but is available as a free download from the Windows Store.

Microsoft is presumably shifting towards an advertising model because of Google’s success. That would also explain why Microsoft is giving away Windows 10, and why they are saying that it’s going to be the ‘last’ version of Windows. It also explains why Microsoft really wants people to log in with their Microsoft account: they can sell ad space destined for those eyeballs for bigger bucks.

Wi-Fi password sharing

Microsoft wants to save you the trouble of sharing Wi-Fi passwords with your friends. Windows 10’s ‘Wi-Fi Sense’ feature automatically sends encrypted Wi-Fi passwords to contacts on Outlook.com, Skype and Facebook.

Wi-Fi Sense has to be enabled for each of your Wi-Fi connections, so there’s really no need to be concerned about its apparent lack of privacy. However, the feature is enabled by default, so you should consider disabling it completely.

Disabling software and devices

In the Windows 10 Terms of Service, Microsoft states that it might “download software updates or configuration changes, including those that prevent you from accessing the Services, playing counterfeit games, or using unauthorized hardware peripheral devices.” This rather alarming statement may only relate to Microsoft software, but that’s not entirely clear. It’s been widely interpreted as an anti-piracy measure.

Again, while Microsoft is ostensibly doing this to improve the customer experience, I’m just not comfortable with the idea of some faceless corporate drone fiddling with my computer remotely.

Cortana looks at personal data

One of the most interesting features of Windows 10 is Cortana, Microsoft’s answer to Apple’s Siri. The goal of both is to make using your device easier, most notably by responding to user voice commands.

Cortana is designed to learn about you: how you write, where you go, what you search for, when you do things, and so on. It gathers this information as you use Windows 10, and gradually gets better at figuring out what you want to do.

As long as Cortana is only using collected data to learn, I don’t really see a problem. But it seems clear that the data being collected is also being transmitted to Microsoft servers. From there, it’s difficult to know for sure how it’s being used, but it’s probably safe to assume it’s being used both to improve Cortana, and for other purposes.

Sharing data with law enforcement

The Windows 10 Terms of Service allow Microsoft to share user data based on nothing more than a “good faith” belief that doing so is required to comply with law enforcement, “protect our customers”, secure the company’s services, or “protect the rights or property of Microsoft”.

This kind of data collection is common on mobile devices, but it’s relatively new for a desktop O/S. Microsoft is at least being reasonably up-front about these things, and settings allow users to disable most of this data collection/sharing. It’s up to the individual user to decide what to disable, and the trade-off is privacy vs. functionality. If you don’t think Microsoft is doing anything insidious with your data, leave the data collection features enabled. If you don’t want to take any chances, turn it all off. As with browser cookies, the collected data can be used in bad or good ways, but without knowing for sure, the more privacy conscious among us will likely turn it all off.

Disabling Windows 10 features to improve privacy

There’s a useful guide for disabling Windows 10’s privacy-compromising features over at Ars Technica.

However: even with all of these features disabled, Windows 10 is still surprisingly chatty with Microsoft’s servers. Is this related to Microsoft’s efforts with advertising? The data people are observing is mostly anonymized, so there’s that. But while we’ve grown accustomed to this kind of activity on web sites and smart phones, it just seems inappropriate for a desktop O/S.

Enterprise customers are likely to see this kind of behaviour as totally unacceptable, so it’s hard to see how Microsoft will ever get businesses to use Windows 10. In fact, Windows 10 could signal the end of the line for Windows, other than as a free, advertising-supported, consumer-targeted system. At one point in my career I worked at a major university, and one of the things I did was recommend software. There’s just no way I would ever recommend Windows 10 for use in a university setting. When Windows 7 support ends, there will likely be a mass exodus of business and education users to Linux.

Even if you’re not particularly worried about all this from a personal perspective, you should consider the ramifications for your work as well. As reported by Dr. Avery Jenkins, using Windows 10 in any medical facility may break privacy laws.

Personally, I’m just not comfortable with the idea of things happening on my computer of which I’m unaware, and over which I have no control. Regardless of Microsoft’s true intent, I don’t want them to have this kind of control. Until and unless Microsoft provides a clear and comprehensive method for disabling all of this unwanted behaviour, I won’t be using Windows 10 on any computers other than for evaluation purposes.

The new user interface reality

Although the user interface for Windows 10 is an improvement over Windows 8.x, it’s still a mixture of new and old style elements.

Before we get into that, a note about terminology: Microsoft likes to confuse everyone, and the frequent re-naming of the new UI and its apps (Metro -> Modern -> Universal) is a great example. Most recently, they’ve decided to call the new style apps Windows Apps, and old style apps Windows Desktop Apps.

But that’s not the whole story. It’s not just apps that have the new look, it’s also most system displays and settings dialogs. So what do I call the visual style of a Windows 10 settings dialog? To keep things simple, I’m going to call the old UI style (as seen in Windows Desktop Apps) ‘classic’ or ‘old’, and the new UI style (as seen in Windows Apps) just ‘new’.

Inconsistencies in Windows 10 settings

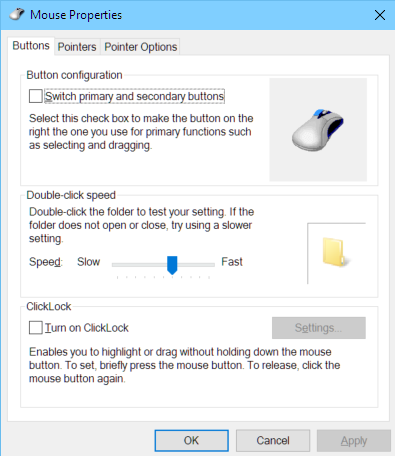

If you click deep enough into a Windows 10 Settings dialog, there’s a good chance you’ll eventually see classic style dialogs.

Examples:

- Settings > Devices > Mouse and touchpad > Additional mouse options

- Settings > System > Advanced display settings > Advanced sizing of text and other items

The crucial difference is that the new style dialogs have no OK/Cancel/Apply buttons, and changes are applied immediately. Classic style dialogs typically have the OK/Cancel/Apply buttons: changes don’t take effect until the OK or Apply button is clicked, and clicking the Cancel button exits without any changes being applied.

The transition from new to old style elements is jarring, and likely to produce confusion in users. Microsoft apparently recognizes this, and they are working to retrofit old-style dialogs as new-style dialogs in Windows 10.

Other oddities exist. New style dialogs sometimes seem to quickly pop up over top of classic style dialogs, as if the old style dialogs are being replaced on the fly. New style dialogs sometimes reappear after they’ve been closed. Old style dialogs sometimes appear beneath new style dialogs, meaning that you must click their (usually flashing) taskbar icon to see them.

Completing this picture of inconsistency, the bulk of Windows 10’s system settings are still only to be found in the good old Control Panel, relatively unchanged since Windows XP. This, despite the very misleading ‘All Settings’ button on the Notifications panel.

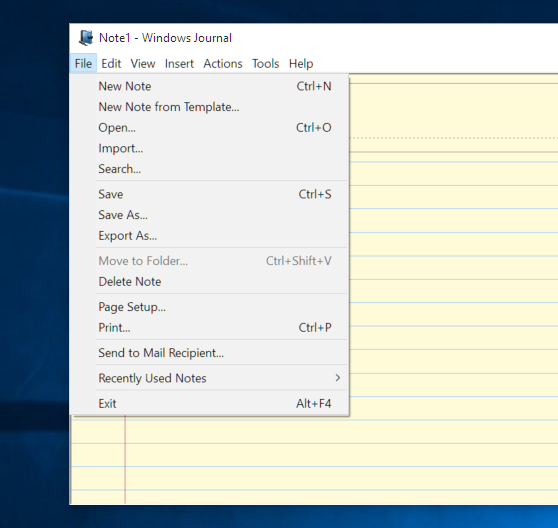

Some new apps use old style dialogs

Oddly, while Microsoft had been pushing the new style UI since Windows 8, they’ve backed away from that practice recently. A notable example is the new style Skype client, which Microsoft has killed, in favour of the classic style client. Even some of the new apps in Windows 10 still look like classic style applications. For example, Windows Journal sports a classic style menu and toolbar.

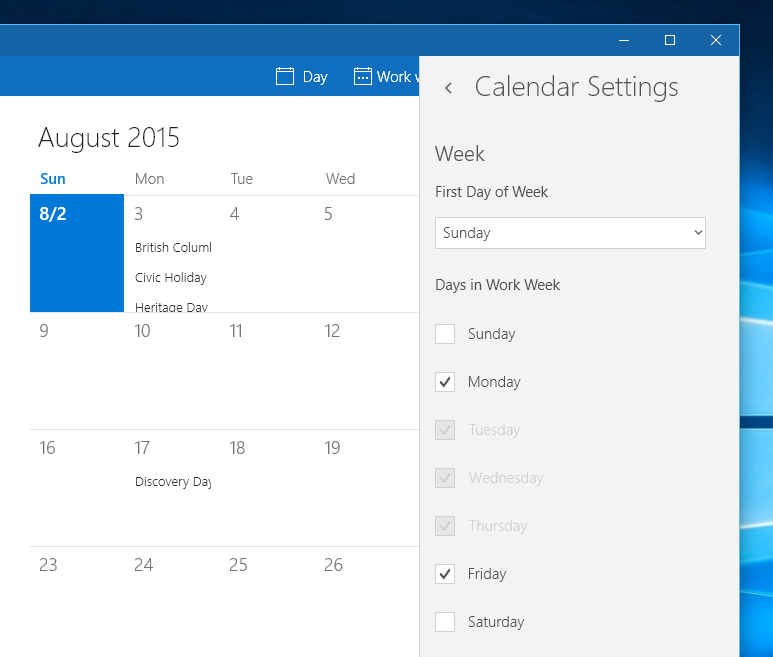

Finding settings in Windows Apps

It can be frustrating to look for settings in new style Windows Apps. In a Windows Desktop App, settings are almost always found in the Tools menu. In a Windows App, you need to look for a special button and click it. That button can look like an arrow, three dots (aka ellipsis), a gear, or the nearly ubiquitous ‘hamburger’, which consists of three parallel, horizontal lines. If you have a smart phone, these buttons are probably familiar, but if you don’t have a smart phone and are coming from Windows 7, you’ll need to learn to recognize them.

Exiting Windows App dialogs

One of the more bizarre aspects of many Windows App dialogs is that there’s no obvious way to close them. This is also fairly typical for smart phone interfaces. To close one of these dialogs, just click elsewhere – outside the frame of the settings dialog. While this may seem simple and intuitive to some people, those of us weaned on more traditional user interfaces may find it unsettling.

The Windows 10 Start menu

The Start menu is back, but it still ain’t what it used to be. Apparently Microsoft still doesn’t pay attention to power users and IT folk, because one of the most effective and efficient ways to streamline the Windows 95/98/NT4/2000/Vista/XP/7 experience is to customize the Start menu, removing clutter and adding folders and shortcuts for commonly-used applications, sites and documents. That’s still not possible in Windows 10. Heavy sigh. Anyway, there are alternatives, including software that enhances or replaces the Start menu, like Stardock’s Start10. It’s also possible to customize the menu that appears when you right-click the Start button, but the process is awkward and limited.

I personally add a completely custom menu to the taskbar by creating a new toolbar folder, adding shortcuts and subfolders to it when I install an application. In place of a Start button, I get a small double arrow icon that generally means ‘click here to expand something’. Sadly, there’s apparently no way to create a normal shortcut to a Windows App. What the hell, Microsoft?

An uncomfortable blend of elements

In any case, starting with Windows 8 and continuing with Windows 10, there’s been a gradual blending of the classic and new UI styles. Anyone who’s been using a smartphone for the past few years will recognize the new UI elements and will probably feel comfortable with them. If you don’t have a smartphone, the transition from a traditional Windows UI (Windows 7 and earlier) to what we find in Windows 10 (and to a lesser extent, Windows 8.x) is going to cause some confusion. The new style dialogs have more in common with smartphone interfaces (and are actually closer to the Mac O/S) than previous versions of Windows.

My main computer – the one I’m using to write this – runs Windows 8.1. I’m able to avoid the Start screen, screen edge menus, Windows Apps and all other new style user interface elements, with the only exceptions being a couple of games. With Windows 10, avoiding new UI elements is not really possible. Windows 10 pushes you to the new Windows Apps, and many of Windows 10’s settings are found only in new style dialogs.

Conclusions

I’m going to keep running Windows 10 on a test computer, but I’m not going to put anything sensitive on that computer. If I see anything happening on that computer that I don’t like, and I can’t find a workaround, I’ll revert it to Windows 7.

If you don’t have a problem with what Microsoft is doing with Windows 10, particularly in terms of privacy, then by all means go ahead and use Windows 10 with the default settings. If you want to use Windows 10 but are worried about privacy, you should review all of its settings and disable anything related to information collection. If these things disturb you and you want nothing to do with Windows 10, stick with Windows 7, which will be supported until 2020. After that, it may be time to look at Linux.

boot13

boot13

One thought on “Windows 10 review”