We’re gradually moving into a world where the software we use every day is maintained remotely, because it runs on or from a remote server, or because it automatically updates itself. This is widely viewed as progress, since the responsibility of protecting everyone from vulnerable software moves away from software users, to software producers. Responsible software producers no longer simply create and sell software, developing and making available updates when necessary; they are taking on the task of deploying those updates to user platforms.

We’re gradually moving into a world where the software we use every day is maintained remotely, because it runs on or from a remote server, or because it automatically updates itself. This is widely viewed as progress, since the responsibility of protecting everyone from vulnerable software moves away from software users, to software producers. Responsible software producers no longer simply create and sell software, developing and making available updates when necessary; they are taking on the task of deploying those updates to user platforms.

There are drawbacks to this approach. Many people — including myself — are reluctant to cede control of the software we use to faceless corporate drones. We are wary of allowing corporate interests control what we see on our computers. With Windows 10, everything is in place to allow Microsoft to sell advertising space on your computer screen. We shudder to think of the nightmare scenarios resulting from bad (and unavoidable) updates.

For those of us who are resistant to these changes, there are options. Most software that automatically updates itself includes settings to disable auto-updates in favour of manual updates. Notable exceptions are Windows 10, and almost all Google and Adobe software.

There are other problems. Once, every update came with release notes and change logs. Increasingly, the details of changes in updates are not published, and users must simply trust that software producers only ever intend to make things better for us. Sadly, that is not always the case. The Windows desktop client for Spotify is a good example: it’s buggy, unstable, crash-prone, and although it is updated frequently, new versions are not documented in any way. Installing Spotify updates is a game of Russian Roulette, and it’s not optional.

Where do we go from here?

Updates should always be optional. Sure, install them by default, but provide settings to allow users to fully control whether and when updates are installed. At the very least, this would make updates much less stressful for business and educational IT staff. How about providing a free version that automatically updates itself and allows advertising, and a reasonably-priced version that allows control over updates and advertising? I’d be willing to pay a few bucks extra to have that kind of control.

Meanwhile, back to reality

Here in the real world, we’ve got more updates from Microsoft and Adobe, many of which are not optional. Some of these updates are not available for free, and are instead prohibitively expensive (e.g. all updates for Windows 7).

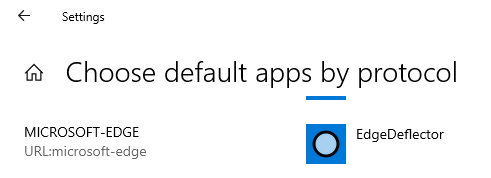

First up it’s Microsoft, with software updates addressing fifty-six vulnerabilities in .NET, Edge, Office, Sharepoint, Visual Studio, VS Code, Windows, and Defender.

First up it’s Microsoft, with software updates addressing fifty-six vulnerabilities in .NET, Edge, Office, Sharepoint, Visual Studio, VS Code, Windows, and Defender.

If you try to count the number of distinct updates, your numbers will vary, depending on what you’re counting. As such, I will no longer be attempting update counts.

You can wade through the details yourself, using the new, ‘improved’ Security Update Guide. You can also find a summary on the official release notes page for this Patch Tuesday.

Several of this month’s updates address critical vulnerabilities that are being actively exploited. Which of course drives home the point that people really need to update, as soon as possible. Which in turn is a strong argument for forcing those updates. Welcome to the new update hell reality.

Adobe has been installing automatic update mechanisms on your computer for a few years now. As with Google software, this is accomplished using a variety of techniques that are also used by malware: to make sure they are always enabled, to reinstall themselves when removed, and to remain hidden as much as possible. While it is possible to remove or disable these update mechanisms, doing so is an exercise in frustration, because they will return, sometimes in a form that’s even more difficult to remove. The only real solution is to avoid using such software.

Adobe has been installing automatic update mechanisms on your computer for a few years now. As with Google software, this is accomplished using a variety of techniques that are also used by malware: to make sure they are always enabled, to reinstall themselves when removed, and to remain hidden as much as possible. While it is possible to remove or disable these update mechanisms, doing so is an exercise in frustration, because they will return, sometimes in a form that’s even more difficult to remove. The only real solution is to avoid using such software.

If you’ve ever opened a PDF file on your computer, there’s a good chance that it opened in Adobe’s free Acrobat Reader. In which case that software is updating itself automatically, using a system service called Adobe Acrobat Update Service.

Adobe released a new version of Reader on February 9: 2021.001.20135. This new version addresses at least twenty-three security vulnerabilities in earlier versions. Since it’s difficult to know exactly when automatic updates will occur, it’s a good idea to check. On Reader’s menu, navigate to Help > About Adobe Acrobat Reader DC. If your version is out of date, select Help > Check for Updates on Reader’s menu to install the new version.

Earlier this week, timed to coincide with Microsoft Patch Tuesday, Adobe released new versions of its PDF authoring tool Acrobat, as well as its free PDF viewer, Reader.

Earlier this week, timed to coincide with Microsoft Patch Tuesday, Adobe released new versions of its PDF authoring tool Acrobat, as well as its free PDF viewer, Reader. boot13

boot13 Still waiting for the vaccine? Trying to avoid going outside? Well, luckily for you, there are plenty of indoor tasks you can work on, like Netflix binge-watching, exercise, and installing software updates on your Windows computers.

Still waiting for the vaccine? Trying to avoid going outside? Well, luckily for you, there are plenty of indoor tasks you can work on, like Netflix binge-watching, exercise, and installing software updates on your Windows computers.

Oracle’s

Oracle’s  There’s a disturbing trend in the world of malware detection: falsely labeling software as malware.

There’s a disturbing trend in the world of malware detection: falsely labeling software as malware. First up it’s Microsoft, with software updates addressing fifty-six vulnerabilities in .NET, Edge, Office, Sharepoint, Visual Studio, VS Code, Windows, and Defender.

First up it’s Microsoft, with software updates addressing fifty-six vulnerabilities in .NET, Edge, Office, Sharepoint, Visual Studio, VS Code, Windows, and Defender. First up, there’s been an

First up, there’s been an  Meanwhile, Google is planning to

Meanwhile, Google is planning to